2012: I heard that the renovations on Villa Grimaldi had been completed under President Michelle Bachelet’s government, herself a victim of detention and torture in Villa Grimaldi. Her father, a general, was killed by Pinochet’s forces. The space had been renovated and outfitted with an education and resource center. An audio tour was available in several languages. Clearly, it was time to go back—this time without a survivor, to try to understand how presence and voice affected my understanding of the space. As before, no taxi driver knew anything about the place and finally, one simply dropped me off at the address on José Arrieta. The outside looked very different, more institutional, though understated. Inside, the homemade sign at the gate, reminding me to behave, is gone. A steel plinth mapped out the timeline. There is no reference to an “us” nor any shared responsibility.

Who is the intended audience or visitor for this renovated place?

Villa Grimaldi, I sensed, had been incorporated into the international memory site industry. Thus yet another layer has been added to the site. I picked up the headphones and transmitter from a young woman at the new resource center and chose the tour in Spanish. The room contained books and charts giving information—listing the detention centers in Santiago, and identifying some of the officers who worked there. As before, there was no one there. Why? This too, I sensed, was a historical question. I asked the person in the resource center if I might be allowed to look in the new buildings. She said there was no one to show me, but sensing my disappointment, she handed me the keys and asked me to lock up and bring them back to her after I was finished. Even without the sign asking me to behave, the keys on the heart-shaped key ring made me feel very responsible.

I put on the headphones and started my walk. The quiet, rhythmic voice of the unidentified female “guide”—I found out later—belonged to a well-known actress of Chilean telenovelas (or soap operas). But without knowing that, I assumed that the young, fresh voice had been untouched by the violence she was describing. The instructions were clear from the outset—I was to move to the different points in the audio tour, marked on the Xeroxed map.

The recorrido followed the same route taken by Matta—the handmade model camp was gone, replaced by a new, glossy, and machine-made replica.

Everything was brittle and white, as in a deep freeze. I recognized the structures, but not the feeling. It had been drained of color, drained of its human history.

It was a different kind of emptying than I had felt the first time I went—the brutality of the demolition had been replaced by the negation of life itself.

I move to the locked iron-gate but now, on my own, I stop to peer out the aperture.

Now, the designated stops are marked by plaques with the audio numbers and new tile markers enacting both the mandate to “fix” in place and update.

But there are some new buildings, locked. I find the key and let myself in. The cases lining the length of the tiled, square building exhibit pieces of metal that the military had attached to the bodies they threw in the ocean so that they wouldn’t float. The button accentuated by the magnifying glass offers proof, if any is still needed, of what happened to the bodies. Now, the site is much more ordered, the paths are clearly marked and illuminated—some of the beauty of the 19th century villa had been restored with wading pools and multiple fountains. The site has been integrated, visually and politically, into the surrounding neighborhood. The neighboring houses are clearly visible. Their view of the “park” must be quite pleasant. The torture site has been domesticated—the visceral pain I felt with Matta has given place to repose. This clearly transmits the sense of a different political moment. With the opening of the new Museum of Memory and Human Rights that same year, it appears that the contestation has given way to a time of acceptance and memorialization.

Later, as I peer behind buildings, I see all the original handmade materials in a heap, under tarps, in a shed behind a building.

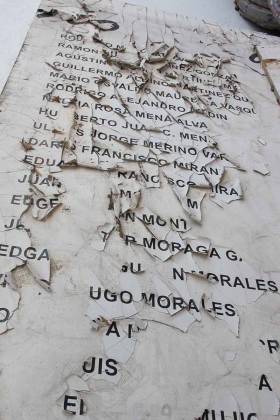

The names of the dead have bled on the sign, reminding us that “forgetting is full of memory.” Memory, clearly, is also full of forgetting.

I feel very alone as I continue the walk-through and, as before, wonder what I am doing there. If Matta needed me to presenciar and acompañar, I realize now how much I needed him to experience Villa Grimaldi. I fumble with the buttons on the digital recorder and feel silly with the headphones even though the site is empty. I get impatient as the voice tells me, in a matter of fact way, about the political acts that lead to the creation of this torture center. The details—the names of the generals, organizations, and so on—overwhelm me. I feel face to face with “History” and I miss the human scale. I feel tempted to pull the headphones off, but resist temptation. When the audio segment comes to an end, I stop, search the map for the next “stop” and move towards it.

I keep walking. The crisp soft voice of the audio, that draws on a great number of testimonies, gives far more detail than Matta did. There are more dates, figures, facts. The separation of data into short bits makes sense, of course—supposing that the listener will have time to move from place to place. I wander as I listen and feel free now to walk into Casas Chile and peer out. I take a photograph and wonder what I’m doing. Does the photo prove that I am here? Or that I was there? But where? This replica did not form part of the torture center that I am ostensibly visiting, knowing full well that the detention center, and the objects, and the people are long gone. I continue on the designated path and listen. The segments are disturbing, not just in their content but in their fragmentation. They start and end abruptly—often after a particularly interesting or disturbing image.

Patio de Abedules—the men were allowed to sit on the bench in the open air for a few minutes a day under strict supervision. Because they could not see, they depended on their sense of smell and developed a secret code of sounds to communicate. Wait, say more! But the audio goes dead.

Cells and Torture Rooms—the women’s cells had a window painted over through which they could see the men being taken to the torture rooms. They could identify the men and their torturers. Next door to them was a room called the parrilla (or grill) where prisoners were stripped, bound to metal bed and tortured with electricity. End of section. No, let me down easy!

The same bland tone speaks of unimaginable brutality and describes the voice of the woman captive with a voice like Edith Piaf’s who sang to drown out the screams of the torture. Even when the voice cites specific testimony, there is no change in tone. As I walk, the voice points out the rose garden, planted in honor of female victims.

Survivors had spoken of smelling roses at the compound, so it seemed fitting to name each one after a woman who died there. Again, the need to individualize terror.

I take in the facts but find it hard to relate to the events and to the space. The voice does not speak to me, and I find the disconnect between the tone and tale distracting. It’s as if we could separate out the different moments, routines, and spaces. The pauses between segments, too, seem very different from Matta’s recounting. His silences were full of memory. His face, body, and mood transmitted his thinking processes and affective swings.

I cannot identify the silences of the audio—they were simply blank nothing, not even tape.

If forgetting and silence are full of memory, full of life, the audio has a hard time capturing that life. I felt dutiful, but not engaged, as I followed the voice around Villa Grimaldi. It was a pedagogical experience; a physical exercise in Never Again.

What does this tour ask of me? The voice thanks me for my visit. It explains that Villa Grimaldi is a material and symbolic trace of State Terrorism under Augusto Pinochet. The explanation clearly lays out the criminal practice linked to neoliberal economic politics. It says that the visit is a look to the past. Still, “we hope” (says the unidentified voice) that it prompts reflection on the present and an impetus to halt human rights abuses throughout the world. If “I” am interested in knowing more, then please visit the web page etc. She also gives me a phone number.

I take the headphones back to the office and ask the woman at the desk about the narration of the audio. She thought they had chosen a young actress with no direct ties to the violent past because they wanted the younger generations to identify.

Villa Grimaldi, then, is no longer about Matta, and trauma, and justice deferred.

It is about getting the next generation to understand their history. This, then, is the very future envisioned by Matta with his booklet, but he is nowhere part of this new post-survivor moment. Memory has been actualized, and now the battle lines have been drawn differently. With Bachelet out of office after the constitutional ban on sequential re-election, right-wing business man Sebastián Piñera became president in 2010. Villa Grimaldi and the Museum of Memory had lost almost half of their operating budget. I spent some time talking with the woman in the visitor’s office. Her father had been a prisoner at Villa Grimaldi who never spoke of his experience, though he has come back to the camp/park/memory site a couple of times. The repose offered by the domestication of Villa Grimaldi and the lulling voice is not as untroubled as it seems. These are still contested spaces, contested presents, and contested pasts.