2006 Pedro Matta is a survivor who, twice a month or so, gives a guided visit to people who want to know about what happened in Villa Grimaldi. Given my work on disappearances in Argentina, colleagues thought I would like to meet him.i He greets me and hands me the English version of a book he has written: “A Walk Through a 20th Century Torture Center: Villa Grimaldi, A Visitor’s Guide.” I tell him that I am from Mexico and speak Spanish. “Ah,” he says, his eyes narrowing as he scans me, “Taylor, I just assumed…”

The space is expansive. It looks like a ruin or a construction site with old rubble and signs of new buildings—a transitional space, part past, part future. I look down at the book Matta gave me, and at the map (above) created by Matta that outlines the route of the visit. It starts at the new entrance, goes to the model of the detention center, then the old portón or gate through which captives were brought in, then along the periphery where the cells and torture rooms used to be, to the memorial wall, and the replica of the water tower where high value captives were kept, then past the few original buildings on the site—the ‘memory room’ and the original swimming pool—down past the memorials, and then up towards the new fountain and pavilion.

This is the route we will take in this section and then again in “Contested Sites” which offers the audio tour following the same route.

Photo: Diana Taylor, 2006

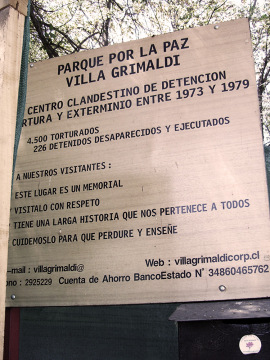

A crude, handmade sign at the entrance, Parque Por la Paz Villa Grimaldi, informs visitors that 4,500 people were tortured here and 226 people were disappeared and killed between 1973 and 1979. This place is simultaneously a torture camp, a memory site, and a peace park. Like many memory sites, it reminds us that this tragic history belongs to all of us and asks us to behave respectfully so that it might remain and continue to instruct. Lesson One, clearly, is that this place is ‘our’ responsibility in more ways than one. But how does it belong to ‘us’? And who is the ‘us’ being invoked and created by the sign?

“This way, please.” Matta walked me over to the small model of the torture camp to help me visualize the architectural arrangement of a place now gone: Cuartel Terranova. “Terranova” (or “new land”) used to designate unexplored territories on ancient maps, and this site indeed, remains unexplored.

Who knew the Chilean military was given to ancient scholarship?

The mock-up is laid out, like a coffin, under a plastic, slightly opaque sunshade that in itself distorts vision.

As in many historically important sites, the model offers a bird’s eye view of the entire area. The difference here is that what I see in the model is no longer there. Even though I am present, I will not experience it “in person.” So, one might ask, what is the purpose of the visit? What can I understand by being physically in a torture center once the indicators have disappeared? Does the space offer up evidence unavailable elsewhere or cues that trigger reactions in visitors? Little beside the sign at the entrance reveals any context. My photographs might illustrate what this place is now, not what it was. So, why? It’s enough for now that I am here in person with Matta who takes me through the recorrido (or “walk-through”). Matta speaks in Spanish; it makes a difference. He seems to relax a little, though his voice is very strained and he clears his throat often. Maybe the words resist being conjured up. Maybe his body belies current attempts to put the “past” behind him. For Matta, it is not just about “what happened” in the historical sense, but also about the ways in which his lived experience at Villa Grimaldi carries into the present.

The compound, originally a beautiful 19th century villa used for upper class parties and then weekend get-togethers for artists and intellectuals, was taken over by DINA, Augusto Pinochet’s special forces, to interrogate the people detained by the military during the massive round-ups.ii Many important artists, thinkers, and activists were disappeared and tortured, including Chile’s President Michelle Bachelet. As thousands of people were captured, many civilian spaces were transformed into makeshift detention centers. The military appropriated sites identified with or run by progressive intellectuals and left-wing movements—Londres 38 had been the office of the Socialist Party; the Center of Humanistic Studies at the University of Chile became the Communications Center for the military, and so on. iii

Villa Grimaldi was one of the most infamous. One of the attractions for the military, I learn later, was that the remote site was close to an airport controlled by Pinochet, head of the Air Forces. This was convenient for loading drugged or dead prisoners on “death flights” and dumping them in the sea.

In the late 1980s, one of the generals sold Villa Grimaldi to a construction company belonging to the Pinochet family to tear down and replace with a housing project. Survivors and human rights activists could not stop the demolition but, after much heated contestation, they did secure the space as a memory site and peace park in 1995.iv Matta, among other survivors and human rights activists, has spent a great deal of time, money, and energy to make sure that the space remains a permanent reminder of what the Pinochet government did to its people.

Three epochs, with three histories, overlap on this space that even now has multiple functions: evidentiary, commemorative, reconciliatory, and pedagogical.

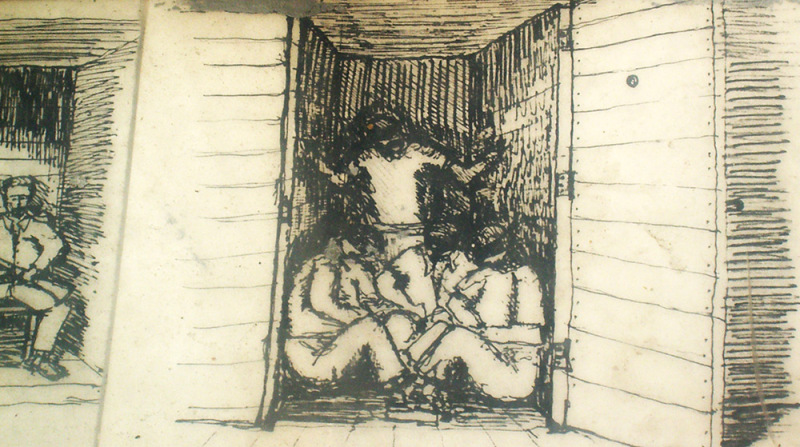

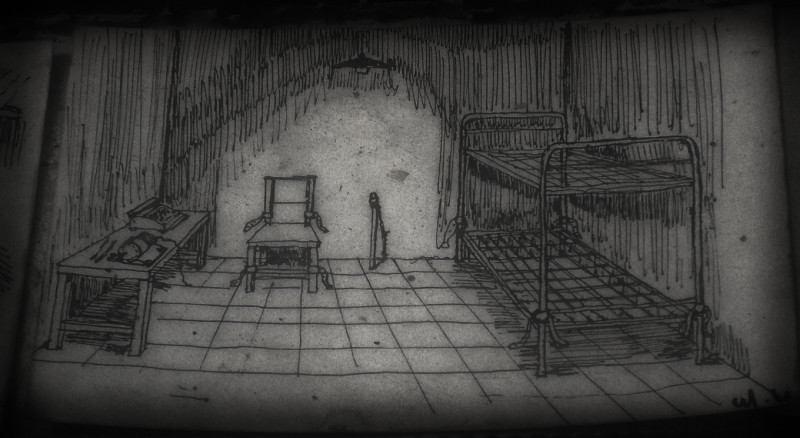

The miniature detention camp positions us as spectators. We stand above the model, looking down on its organizational structure. The model was built, Matta told me, by students of architecture using his and other survivors’ plans. The main entrance to the top left allowed passage for vehicles that delivered the hooded captives up to the main building. Matta’s language and my imagination populate the inert space. He points to the tiny copy of the large main building that served as the center of operations for DINA—here the military planned who they would target and evaluated the results of the torture sessions. The officer in charge of Villa Grimaldi and his assistants had offices here, and there was a mess hall for officers. The space housed the archives and a short-wave radio station that kept the military personnel in contact with their counterparts throughout South America. Plan Condor, the transnational network of repressive military regimes operating in Latin America, in cooperation with the C.I.A., shared intelligence and helped persecute progressive leaders and militants on the run.v In the small buildings along the perimeter to the left, the prisoners were divided up, separated, and blindfolded—men here, women there. Miniature drawings made by survivors line the periphery—hooded prisoners pushed by guards with rifles for their thirty seconds at the latrines; a hall of small locked cells guarded by an armed man; a close-up drawing of the inside of one of the cells in which a half dozen shackled and hooded men are squeezed in tightly; an empty torture chamber with a bare metal bunk bed equipped with leather straps, a chair with straps for arms and feet, a table with instruments; an image of the torturers.

Torture is very literal. Breaking bodies becomes a way of breaking resistance. The fractures in society become the fractures on the body. The images show how literally, too, the objects reference behaviors. I know exactly what happened there/here. Matta points to other structures on the model. It is clear that the displacement offered by the model gives him a sense of control—he no longer needs to fully relive the image to describe it; he can externalize and point to it over there. The violence, in part, can be transferred to the archive, materialized in the small evidentiary mock-up. He is explicit about the criminal politics, and very clear in his condemnation of the C.I.A.’s role in the Chilean crisis. His blue eyes pierce me and then he remembers I am not that audience—an audience but not that audience.

Looking down at the model in relationship to the larger space, I see we are standing on the site of the main building, usurping the military’s place. Looking offers me the strange fantasy of seeing or grasping the “whole,” the fiction that I can understand systemic criminal violence even as I position myself simultaneously in and above the fray. I am permitted to identify without identifying. I am not implicated except to the degree that I can understand the information transmitted to me by the mock-up and Matta, my guide. This happened there, back then, to them, by them… Recounting performs the spatial and temporal displacement. The encounter, at this point, is about representation and explication of the facts. I take photographs, wondering how the tenuous “evidentiary” power of the photo might extend the fragile evidentiary claim of the model camp. I know what happened at Villa Grimaldi, of course, but wonder if being there helps me know it differently. Can I, with my camera, do anything to further make visible the criminal violence?

The “other” violence, the economic policies that justified and enabled the breaking of bodies, remains safely outside the frame.

We look up and around at the “place” itself. There’s not much to see of the former camp. The remains of a few original structures and replicas of isolation cells and a tower dot the compound, emptied though not empty—empty of something palpable in its absence. No history. No one responsible. Activists planted rows of birch trees (abedules), I learned later, to symbolize the fragile and solitary condition of the ex-prisoners, along with their resistance.vi With the camp demolished, Matta informs and points out, but he does not seem to connect personally or emotionally to what he describes. Some objects have been re-constructed and placed to support the narration—”this happened here.” A model of “Casas Chile,” one meter by two meters, forced four or five prisoners to stand upright for extended periods of time. They were called that by the armed forces as an ironic put down of Salvador Allende’s initiative to provide the poor with housing—small and cramped though it was.

Matta told me later that he had learned to sleep standing up in one of those cells.

I imagine some visitors must actually try to squeeze themselves into the tiny, upright isolation cell. They might even allow someone to close the door. Does simulation allow people to feel or experience the camp more fully than walking through it? Possibly. Rites involving sensory deprivation prepare members of communities to undertake difficult or sacred transitions by inducing different mental states. The basic idea—that people learn, experience, and come to terms with past/future behaviors by physically doing them, trying them on, acting them through, and acting them out—is the underlying theory of ritual, older than Aristotle’s theory of mimesis, and as new as theories of mirror neurons that explore how empathy and understandings of human relationality and intersubjectivity are vital for human survival (Gallese 2001). But these reconstructed cells disconcert me. I am embarrassed to even think of entering in Matta’s presence—he was subjected to this cruelty, not me. How can I pretend to experience what he did? Rather the opposite: the less I actually see intensifies what I imagine happened here. My mind’s eye—my very own staging area—fills the gaps between Matta’s formal matter-of-fact rendition and the terrifying things he relates.

Matta walks towards the original entryway—the massive iron-gate now permanently sealed, as if to shut out the possibility of further violence.

From this vantage point, it is clear that another layer has been added to the space. A wash of decorative tiles, chips of the original ceramic found at the site, form a huge arrow-like shape on the ground pointing away from the gate towards the new “peace fountain” (“symbol of life and hope,” according to Matta’s booklet) and a large performance pavilion. The architecture participates in the rehabilitation of the site.

The cross-shaped layout moves from criminal past to redemptive future. Matta ignores that for the moment—he is not in the peace park. This is not the time for reconciliation. His traumatic story, like his past, weighs down on all possibility of a future. He continues his recorrido through the torture camp.vii

Matta speaks impersonally, in the third person, about the role of torture in Chile—one half million people tortured and 5,000 killed out of a population of 8 million. I do the math…1 in 16. There were more tortures and fewer murders in Chile than in neighboring Argentina where the Armed Forces permanently disappeared 30,000 of their own people. Pinochet chose to break rather than eliminate his “enemies”—the population of ghosts, or individuals destroyed by torture, thrown back into society would be a warning to others. Matta speaks about the development of torture as a tool of the state from its early experimental phase to the highly precise and tested practice it became. Matta’s tone is controlled and reserved. He is giving archival information, not personal testimony, as he outlines the daily workings of the camp, the transformation of language as words were outlawed. “Crimenes,” “desaparecidos,” and “dictadura” (“crimes,” “disappeared,” and “dictatorship”) were replaced by “excesos,” “presuntos,” and “gobierno militar” (“excesses,” “presumed,” and “military government”).

As we walk, he describes what happened where, and I notice that he keeps his eyes on the ground, a habit born of peering down from under the blindfold he was forced to wear.

The shift is gradual—he begins to reenact ever so subtly as he re-tells. He moves deeper into the death camp—here, pointing at an empty spot: “Usually unconscious, the victim was taken off the parrilla (metal bed frame), and if male, dragged here.” (Matta n.d., 13) Maybe the lens will grasp what I cannot grasp. Looking down, I see the colored shards of ceramic tiles and stones that now mark the places where buildings once stood and the paths where victims were pushed to the torture chambers. As I follow, I too know my way by keeping my eyes on the ground: “Sala de tortura” (“torture chamber”), “Celdas para mujeres detenidas” (“cell for detained women”).

I follow his movements but also his voice—that draws me in. Gradually, his pronouns change—they tortured them becomes they tortured us. He brings me in closer. His performance animates the space and keeps it alive. His body connects me to what Pinochet wanted to disappear, not just the place but the trauma. Matta’s presence performs the claim, embodies it, le da cuerpo. He has survived to tell. Being in place with him communicates a very different sense of the crimes than looking down on the model. Walking through Villa Grimaldi with Matta brings the past up close, past as actually not past. Now. Here. And in many parts of the world, as we speak. I can’t think past that, rooted as I am to place suddenly restored as practice. I too am part of this scenario now; I don’t need to lock myself up in the cell to be doing. I have accompanied him here. My eyes look straight down, mimetically rather than reflectively, through his downturned eyes. I do not see really; I imagine. I presenciar; I presence (as active verb). Embodied cognition, neuroscientists call this, but we in theatre have always understood it as mimesis and empathy—we learn and absorb by mirroring other people. I participate not in the events but in his transmission of the affect emanating from the events. My presencing offers me no sense of control, no fiction of understanding. He walks through the Patio de Abedules, he sits on the semi-circle that remains from the camp, he tells. When he gets to one of the original trees, used to torture prisoners in various ingenious ways, he acts out some of the positions he and others endured. He suffered a permanent lesion in his shoulder, he told me, and his heart was affected. In front of where the torture rooms stood, he relates that the tortured body begins to release water from all its pores. Although completely dehydrated, the person cannot drink water because the remaining electricity in the body would electrocute him or her. It takes a few hours to de-electrify. And electricity, he continued, makes the body contract, so the torturers would strap the victim down with a leather strap. Prisoners were left with lasting damage to their spinal column, and often their sphincter. When he gets to the memorial wall marked with the names of the dead (built twenty years after the violent events), he breaks down and cries. He cries for those who died but also for those who survived.

“Torture,” he says, “destroys the human being. And I am no exception. I was destroyed through torture.”

This is the climax of the tour. The past and the present come together in this admission. Torture works into the future yet it forecloses the very possibility of future. The torture site is transitional, but torture itself is transformative—it turns societies into terrifying places and people into zombies (Godoy-Anativia 1997).

When Matta leaves the memorial wall, his tone shifts again. He has moved out of the death space. Now, he is more personal and informal in his interaction with me. We talk about how other survivors have dealt with trauma, about similarities and differences with other torture centers and concentration camps. He says he needs to come back. The walk-through reconnects him with his friends who were disappeared. Whenever he visits with a group who is interested in the subject, he feels he is doing what he wishes one of his friends had done for him had he been the one disappeared. Afterwards, he goes home physically and emotionally drained, he says, and drinks a liter of fruit juice and goes to sleep—he doesn’t get up until the following morning. His body still hurts from the torture, and he has developed debilitating after-effects. We continue to walk, past the replica of the water tower where the high value prisoners were isolated, past the “sala de la memoria” (“memory room”)—one of the few remaining original buildings that served as the photo and silkscreen rooms. At the pool, also original, he tells one of the most chilling accounts told to him by a collaborator. At the memory tree, he touches the names of the dead that hang from the branches, like leaves. Different commemorative art and memorials for the dead have been installed by some of the political parties and organizations most virulently hit by the Armed Forces—the Chilean Communist Party and the MIR (the Revolutionary Left Movement) among others line the periphery like small grave plots.

Near the exit, a large sign with names of the dead, reminds us that

“El olvido esta lleno de memoria” (“forgetting is full of memory”).

And of course, the ever hopeful Nunca Más. He barely notices the fountain—the Christian overlay of redemption was the government’s idea, clearly.

After we leave the site, I invite Matta to lunch at a nearby restaurant that he recommends. He tells me about his arrest in 1975 for being a student activist, his time as a political prisoner in Villa Grimaldi, his exile to the U.S. in 1976, and his work as a private detective in San Francisco until he returned to Chile in 1991. He used his investigative skills to gather as much information as possible about what happened in Villa Grimaldi, to identify the prisoners, and name the torturers stationed there. One day, he says, he was having lunch in this same restaurant after one of the visits to Villa Grimaldi when an ex-torturer walked in and sat at a nearby table with his family. They were having such a good time. They looked at each other and Matta got up and walked out.